The Battle of Saratoga

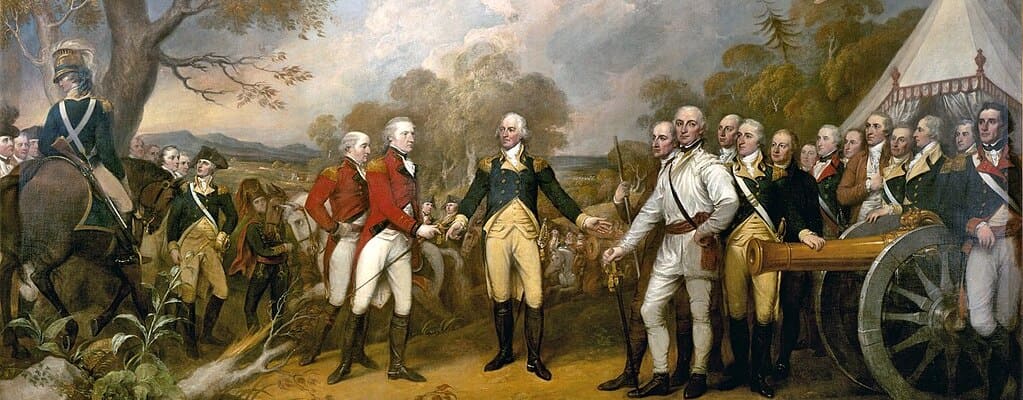

The surrender of the British General John Burgoyne at Saratoga. Image courtesy of John Trumbull, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Story of the Battles of Saratoga

“…one of the Greatest battles that Ever was fought in Amarrca…”

~ Major Henry Dearborn

The Neilson House in the American Camp served as the headquarters for Generals Benedict Arnold and Enoch Poor.

The Revolutionary War is enshrined in American memory as the beginning of a new nation born in freedom. In this memory the conflict was quick and easy, the adversaries are little more than cartoon-like tin soldiers whose brightly colored uniforms make them ideal targets for straight-shooting American frontiersmen.

In actuality, the very year of Independence was a time of many military disasters for the fledgling republic; the first year of its existence was almost its last. New York was the stage for much of the drama that unfolded.

During the summer of 1776, a powerful army under British General Sir William Howe invaded the New York City area. His professional troops defeated and outmaneuvered General George Washington’s less trained forces. An ill advised American invasion of Canada had come to an appalling end, its once confident regiments reduced to a barely disciplined mob beset by smallpox and pursuing British troops through the Lake Champlain Valley.

As 1776 ended, the cause for American Independence seemed all but lost. It was true that Washington’s successful gamble at the battles of Trenton and Princeton kept hopes alive, but the British were still holding the initiative. Royal Garrisons held New York and its immediate environs, Newport, Rhode Island and Canada. Additionally the Royal Navy allowed the British to strike at will almost anywhere along the eastern seaboard.

In hopes of crushing the American rebellion before foreign powers might intervene, the British concocted a plan to invade New York from their base in Canada in 1777. Essentially, two armies would follow waterways into the Rebel territory, unite and capture Albany, New York. Once the town was in their possession, these British forces would open communications to the City of New York, and continue the campaign as ordered. It was believed that by capturing the Hudson River’s head of navigation (Albany) and already holding its mouth (the City of New York), the British could establish their control of the entire river. Control of the Hudson could sever New England-the hot bed of the rebellion-from the rest of the colonies.

Scene from a Re-enactment at the Saratoga Battlefield. Photo by Tom Killips 10/12/2002

The architect of the plan, General John Burgoyne, commanded the main thrust through the Lake Champlain valley. Although the invasion had some initial success with the capture of Fort Ticonderoga, the realities of untamed terrain soon slowed the British triumphant advance into an agonizing crawl. Worse for the British, a major column en route to seek supplies in Vermont was overrun, costing Burgoyne almost irreplaceable 1000 men. Hard on the heels of this disaster, Burgoyne’s contingent of Native Americans decided to leave, word came from the west that the second British column was stalled by the American controlled Fort Stanwix and that the main British army would not be operating near the city of New York. Although his plans were unraveling, Burgoyne refused to change his plans and collected enough supplies for a dash to Albany.

For the Americans, the British delays and defeats had bought them enough time to re-organize and reinforce their army. Under a new commander, General Horatio Gates, the American army established itself at a defensive position along the Hudson River called Bemis Heights. With fortifications on the flood plain and cannon on the heights, the position dominated all movement through the river valley. Burgoyne’s army was entirely dependent upon the river to haul their supplies, and the American defenses were an unavoidable and dangerous obstacle.

Learning of the Rebels’ position, Burgoyne attempted to move part of his army inland to avoid the danger posed by the American fortifications. On September 19th 1777, his columns collided with part of General Gates’ army near the abandoned farm of Loyalist John Freeman. During the long afternoon, the British were unable to maintain any initiative or momentum. Pinned in place, they suffered galling American gunfire as they strove to hold their lines. Late in the day, reinforcements of German auxiliary troops turned the tide for Burgoyne’s beleaguered forces. Although driven from the battlefield, the British had suffered heavy casualties and Gates’ army still blocked his move south to Albany.

The Surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga, New York. 17 October 1777. Painting by John Trumbull and taken from the Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia.

General Burgoyne elected to hold what ground he had and fortify his encampment, hoping for assistance from the City of New York. On October 7th, with supplies running dangerously low and options running out, Burgoyne attempted another flanking move. The expedition was noticed by the Rebels who fell upon Burgoyne’s column. Through the fierce fighting the British and their allies were routed and driven back to their fortifications. At dusk, one position held by German troops, was overwhelmed by attacking Americans. Burgoyne had to withdraw to his inner works near the river and the following day tried to withdraw northward toward safety. Hampered by bad roads made worse by frigid downpours, the British retreat made only eight miles in two days to a small hamlet called Saratoga; Gates’ army followed and surrounded Burgoyne and his army. With no other option Burgoyne capitulated on 17 October 1777.

The American victory at Saratoga was a major turning point in the war for Independence, heartening the supporters of independence and convincing France to enter in the war as an ally of the fledgling United States. It would be French military assistance that would keep the rebel cause from collapse and tip the balance at Yorktown, Virginia in 1781 – winning America its ultimate victory as a free and independent nation. The war also would reach to nearly every quarter of the globe as Spain and the Netherlands would become involved. But more importantly ideals of the rebel Americans would be exported as well, inspiring people throughout the world with the hope of liberties and freedom.

[The preceding information was provided by the staff at the Saratoga National Historical Park.]

Life of a Revolutionary Soldier

Although many Americans turned up from miles away to fight the British, the Continental Army had continual trouble keeping its enlistment up. In times of need, the army might resort to recruiting slaves, pardoned criminals, British deserters, and prisoners of war. The lack of enthusiasm for enlisting occurred for a number of reasons. The colonists' previous experience with a regular army was that with the British, who were not very well liked, as the Boston Massacre had shown. Farmers did not want to leave their fields untended for long periods of time. States competed with the Continental Congress to keep men in the militia. The pay was low and uncertain, especially in a period of inflation. No pension system existed to compensate a soldier or his family for injuries or deaths in the line of duty.

Life as a soldier was not very pleasant, either. Disease was common; it would often spread through entire camps. The soldiers often slept under the stars, or when they did have tents, the soldiers might not have a blanket. They sometimes awakened from a night of sleeping only in their summer clothing and would see frost on the ground. Food was frequently scarce. Salt and other seasonings were amenities soldiers would almost always do without. When there was no food at all, soldiers went hungry for days at a time before finding turnips, nuts, or other subsistence. When soldiers did receive real beef or other meats, they rarely had cooking utensils to use. Nevertheless, raw meat was preferable to nothing at all. It is a wonder that the American side won the war at all.

[Written by Kris Donhowe with information from Private Yankee Doodle by J.P. Martin]

The American Army fire their muskets on the British. The Americans are mounting a 3 pronged response to the 3-column British advance under the command of Horatio Gates. In the first battle, the Americans used no artillery. The Battle of Saratoga was extremely intense for an 18th-century battle because both armies were well supplied and rested. Soldiers fired and advanced in columns because of the inaccuracy of musket fire.

People at Saratoga

The events of the battles of Saratoga brought thousands of strangers to the once peaceful farmlands along the Hudson River. Essentially two good-sized “cities” moved into the area.

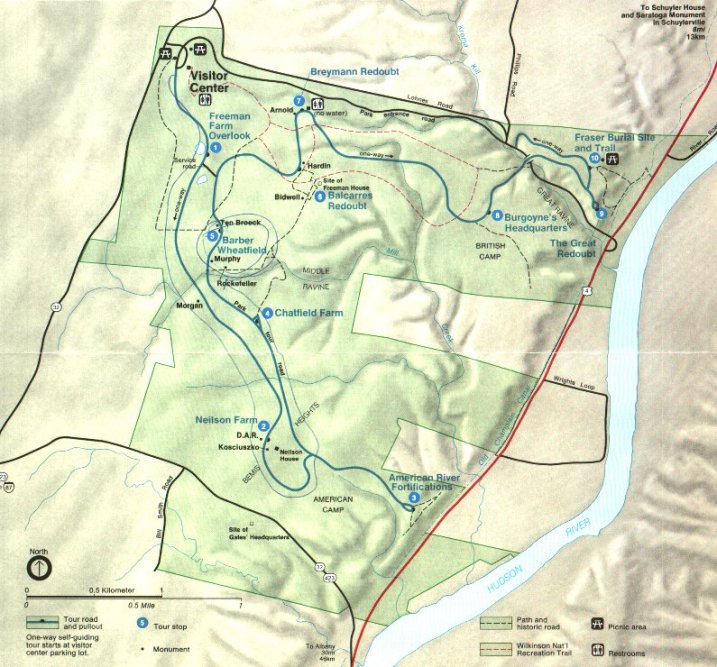

British General John Burgoyne’s army arrived with some 7500 British regulars, German Auxiliary Troops, Loyal Americans, Canadian militia and small contingents of Native Americans. The impact of such a mobile army, including headquarters, officer and troop tents, weapons, cooking and baking areas, hospital, artillery, pack animals and more, engulfed an area about one square mile, from Freeman’s Farm north and west to the Great Redoubt.

American forces were numerically superior - approximately 8500 troops in September grew to almost 12,000 by the second battle in October 1777. They too dominated an area about one square mile, which was located south of the British camps in an area called Bemis Heights. Commanded by Major General Horatio Gates, the American forces included New Englanders, New Yorkers, Virginians, Marylanders, Pennsylvanians, Native Americans, Canadians, French volunteers and one Pole-Thaddeus Kosciusko. Women and children accompanied both armies, sharing the hardships and dangers that army life presented.

Local inhabitants reacted in various ways to this occurrence. Some like patriot John Neilson packed up their possessions and removed their families from harm’s way. Others, like farmer John Freeman and his twelve year-old-son Thomas, elected to stay and fight for their beliefs: Freeman and his son serving with a contingent of Loyalists in Burgoyne’s army.

For farmers, the impact of the armies’ presence on their land was devastating. Many acres of trees were felled to be used in fortifications or utilized as fuel. Crops, gardens and hayfields were used or trampled by the troops. John Neilson, whose farm was an American mid-level headquarters, suffered losses of crops, hay and many hundreds of feet of fences. John Freeman’s farm would be in the crossfire of both battles and irretrievably lost with Burgoyne’s retreat.

Following the surrender, Burgoyne’s British and German troops were forced to march back to Boston. Some were later interned, many sailed back to Great Britain under the promise they would not fight in the war again and some drifted into the countryside and became new Americans. Gates’ Continentals were dispatched to George Washington’s forces in Pennsylvania, just in time to spend a grueling winter at Valley Forge.

The War for Independence would have six more years of uncertainty and danger for local inhabitants. Some, like John Neilson would improve his farm, be elevated to an officer’s rank in the local militia and raise a family on his very prosperous farm. Others were far less fortunate: John Freeman, having lost his farm, lived with his family as refugees along the shores of Lake Champlain. In 1778, John, his wife and most of their children died from smallpox.

[The preceding information was provided by the staff at the Saratoga National Historical Park.]

Building a National Historical Park

The guns had barely fallen silent at Saratoga when the first visitors to the battle sites arrived. Momentous events happened here along the banks of the Hudson River in 1777: a decisive American military victory kept alive the hopes and dreams of liberty for a new nation born in the turmoil of a Revolutionary War; dangerous ideals of freedom were placed squarely before people world-wide. With such credentials, it is no surprise that the battlefield has attracted interest of politicians, generals, scholars and everyday visitors from all over the world.

Having spent the summer and autumn of 1777 dealing with British forces in the mid-Atlantic states, it was no surprise that General George Washington would wish to see the site of the Saratoga battles. Washington visited the battlefield at Saratoga when he came to the area as a guest of General Philip Schuyler in1783. Future presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison followed him, and the former president John Quincy Adams spent a day visiting while staying in Saratoga Springs in 1843.

Saratoga Monument, obelisk, Saratoga National Historic Monument, Saratoga, NY

Through the 19th and early 20th centuries, different individuals and organizations attempted to preserve the memory of the events of 1777. The Saratoga Monument was completed in the Village of Victory in 1882, commemorating the campaign and American triumph. Nineteen twenty six, with the sesquicentennial of the Battles approaching, saw the preservation of the Saratoga Battlefield under the aegis of New York State. The following year, over 160,000 people visited the newly established park. They viewed great pageant with a cast of thousands held on the fields in Stillwater and visited the 1777 home of John Neilson and a newly constructed “Blockhouse” museum.

With improved roads, and a staff of guides at the museum, Saratoga Battlefield became a popular site to visit. National figures such as Admiral Richard E. Byrd, foreign dignitaries and descendants of many who fought at Saratoga, visited over the years. One particularly interested visitor was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Governor of New York State and later, President. During his term as governor, Roosevelt conducted guided tours for governors of five states that were his guests in New York.

Visitors can learn more about the park by visiting www.nps.gov/sara.

[The preceding information was provided by the staff at the Saratoga National Historical Park.]

History

On September 19, 1777, the Royal army advanced upon the American camp in three separate columns within the present-day towns of Stillwater and Saratoga. Two of them headed through the heavy forests covering the region; the third, composed of German troops, marched down the river road. American scouts detected Burgoyne's army in motion and notified Gates, who ordered Col. Daniel Morgan's corps of Virginia riflemen to track the British march. About 12:30 p.m., some of Morgan's men brushed with the advance guard of Burgoyne's center column in a clearing known as the Freeman Farm, about a mile north of the American camp. The general battle that followed swayed back and forth over the farm for more than three hours. Then, as the British lines began to waver in the face of the deadly fire of the numerically superior Americans, German reinforcements arrived from the river road. Hurling them against the American right, Burgoyne steadied the wavering British line and gradually forced the Americans to withdraw. Except for this timely arrival and the near exhaustion of the Americans' ammunition, Burgoyne might have been defeated that day. Though he held the immediate field of battle, Burgoyne had been stopped about a mile north of the American line with his army roughly treated. Shaken by his "victory," the British commander ordered his troops to entrench in the vicinity of the Freeman Farm and await support from Clinton, who was supposedly preparing to move north toward Albany from New York City.

For nearly three weeks he waited but Clinton did not come. By now Burgoyne's situation was critical. Faced by a growing American army without hope of help from the south, and with supplies rapidly diminishing, the British army became weaker with each passing day. Burgoyne had to choose between advancing or retreating. He decided to risk a second engagement, and on October 7 ordered a reconnaissance-in-force to test the American left flank. Ably led and supported by eight cannons, a force of 1,500 men moved out of the British camp. After marching southwesterly about three-quarters of a mile, the troops deployed in a clearing on the Barber Farm. Most of the British front faced an open field, but both flanks rested in woods, thus exposing them to surprise attack. By now the Americans knew that Burgoyne's army was again on the move and at about 3 p.m. attacked in three columns under Colonel Morgan, Gen. Ebenezer Learned, and Gen. Enoch Poor.

Repeatedly the British line was broken, then rallied, and both flanks were severely punished and driven back. Gen. Simon Fraser, who commanded the British right, was mortally wounded as he rode among his men to encourage them to make a stand and cover the developing withdrawal. Before the enemy's flanks could be rallied, Gen. Benedict Arnold -who had been relieved of command after a quarrel with Gates- rode onto the field and led Learned's brigade against the German troops holding the British center. Under tremendous pressure from all sides, the Germans joined a general withdrawal into the fortifications on the Freeman Farm. Within an hour after the opening clash, Burgoyne lost eight cannon and more than 400 officers and men. Flushed with success, the Americans believed that victory was near. Arnold led one column in a series of savage attacks on the Balcarres Redoubt, a powerful British fieldwork on the Freeman Farm. After failing repeatedly to carry this position, Arnold wheeled his horse and, dashing through the crossfire of both armies, spurred northwest to the Breymann Redoubt. Arriving just as American troops began to assault the fortification, he joined in the final surge that overwhelmed the German soldiers defending the work. Upon entering the redoubt, he was wounded in the leg. Had he died there, posterity would have known few names brighter than that of Benedict Arnold. Darkness ended the day's fighting and saved Burgoyne's army from immediate disaster.

That night the British commander left his campfires burning and withdrew his troops behind the Great Redoubt, which protected the high ground and river flats at the northeast corner of the battlefield. The next night, October 8, after burying General Fraser in the redoubt, the British began their retreat northward. They had suffered 1,000 casualties in the fighting of the past three weeks; American losses numbered less than 500. After a miserable march in mud and rain, Burgoyne's troops took refuge in a fortified camp on the heights of Saratoga. There, an American force that had grown to nearly 20,000 men surrounded the exhausted British army. Faced with such overwhelming numbers, Burgoyne surrendered on October 17, 1777. By the terms of the Convention of Saratoga, Burgoyne's depleted army, some 6,000 men, marched out of its camp "with the Honors of War" and stacked its weapons along the west bank of the Hudson River. Thus was gained one of the most decisive victories in American and world history.